National institutions must lead by example

regarding the publication of official documents

Click on the

octopus to return to

the top of the page

The original COMEX-based NORMAM-15/DPC saturation procedures,

which were adopted and published in Portuguese and English by the

Brazilian Navy Directorate of Ports and Coasts in June 2011, are an

evolution of the previously published COMEX MT-92 procedures that

are still in force in the French regulations.

They have been later on published and reinforced in 2019 in the CCO

Ltd Diving Management Study #5 “Implement Normam-15/DPC

saturation diving procedures” that rigorously conforms to this first

2011 edition, except that the gas values for the descent and the

storage periods that were missing in the official document have been

provided by Jean-Pierre Imbert, who worked as the COMEX company

diving manager at the time and who can be considered the lead author

of many COMEX procedures. The reasons for the reinforcements were

that several improvements to diving procedures have been adopted in

the industry since the creation and official publication of this table in

2011, necessitating the incorporation of these updates to keep this CCO

Ltd study current. Therefore, some complementary procedures from

the latest NORSOK standards U-100, the Diving Medical Advisory

Committee (DMAC), the International Marine Contractors Association

(IMCA), the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE), and the French

Ministry of Labour are included in this study, along with conclusions

from relevant research such as the paper “A review of accelerated

decompression from heliox saturation in commercial diving

emergencies” by Jean-Pierre Imbert, Jean-Yves Massimelli, Ajit

Kulkarni, Lyubisa Matity, and Philip Bryson.

Incorporating these procedures into the original COMEX-based ones

results in a safe, cost-free alternative to recent saturation methods,

enabling operations at depths up to 350 m. This approach has been

favorably received by several scientists and companies, as it is cited in

multiple scientific studies and frequently downloaded. We can

therefore consider that, currently, the only more modern procedures

are those based on the sliding windows concept invented by Jean-

Pierre Imbert. However, these tables are available only privately and

are not freely accessible to the public.

It is also worth noting that two updates published by Brazilian

authorities were not considered, as these documents were only

available in Portuguese, and many in the scientific community, including

the lead author of these procedures, were unaware of them.

In 2023, the Brazilian authorities superseded the NORMAM-15/DPC

procedures with the NORMAM-222/DPC procedures, published both in

Portuguese and English. That has resulted in the need to compare

these new guidelines with those previously published in 2011 to

evaluate the evolution of these saturation diving procedures and,

consequently, determine whether they still conform to the original

COMEX procedure, whether additional reinforcements have been

introduced to comply with the latest safety practices, and whether

changes have been made that cause them to no longer conform to the

original decompression model.

Comparison method

A point-by-point comparison method was used to ensure no details

were missed. Thus, this involved writing the procedure steps into two

columns: one for Normam 15/DPC-2011 and one for Normam-

222/DPC. These steps were arranged side by side for easy

comparison, with chapters and sections separated by sufficient space

to avoid confusion.

As previously mentioned, Normam-222 saturation procedures were

compared only with those of the 2011 version of Normam-15, as the

"Study #5 CCO Ltd", published in 2019, is built on them and does not

incorporate the previously mentioned updates from the Brazilian

authorities. This comparison, available in the CCO Ltd Diving

Management Study #13, "Gap analysis between the Normam-15/DPC-

2011 and Normam-222/DPC Saturation Diving Procedures", showed

some differences, so we have contacted the Brazilian authorities for

clarification, and they have kindly responded. Their answers have been

introduced in the sections of this gap analysis that raised questions.

Results

The first point to note is that the English version should not be

considered valid, as essential elements such as the calculation method

for stabilization periods between the surface and 100 m have been

omitted. This omission results in the formula for exposures between

100 and 180 m being applied to both types of exposures, contrary to

the Portuguese version, which faithfully follows the original procedure

on this point. In addition, translations are not always precise. This

resulted in the use of the Portuguese version, which was translated

using the “DeepL” software, as well as the artificial intelligence

programs “Mistral” and “ChatGPT” when necessary. Nevertheless, for

convenience, the texts from the English version were used when they

were compliant. The cover of this English-translated version mentions

that it is not considered an original legal document. However, why

publish documents that are not verified to conform to the original? We

suppose there are sufficiently talented translators in Brazil who could

have done this work properly. To answer our remark regarding this

incorrect edition, the Brazilian authorities said that this item will be

adjusted in a future revision.

To conclude

Some may argue that what we propose is an unattainable ideal and

that maintaining the status quo is the only realistic option.

On the contrary, we believe that continuing along the current path risks

the collapse of the system initially designed to regulate and support

professional practices.

Such a collapse could lead to a world governed not by fairness and

merit, but by a handful of influential organizations competing to impose

their economic models, often relying on clientelism-based practices.

In such a world, professional organizations, companies, and individuals

would lose their rights and autonomy. Progress would depend not on

competence or innovation, but on securing the political favor of

dominant institutions. This scenario is the antithesis of the "democratic

world" so often promised by politicians.

To contribute to designing the "ideal diving world", we hold that the

principle of "every person to their trade", also known as "deference to

expertise", must be the rule. Therefore, states, supranational, and

international organizations must adopt transparent, science-based, and

consistent standard-setting practices. These practices should be open

to analysis, discussion, and, when necessary, criticism by professional

bodies and individuals.

To truly earn their legitimacy, national institutions must lead by

example. There is no other path forward.

Discussion

We must first emphasize that, as demonstrated in the CCO Ltd Diving

Management Study #5, it would have been possible to reinforce the

initial procedure, and thus avoid entering a process of validating a new

decompression procedure, by adding safety practices currently in use

in the diving industry without altering the key elements of the

decompression procedure, which include:

1.

The compression rate to the “storage depth”, stabilization stops,

and stabilization periods before diving, which are calculated to

manage phenomena such as compression arthralgia, narcosis,

and High Pressure Nervous Syndrome (HPNS).

2.

The maximum descent and ascent rates from and to the bell

3.

The maximum excursion distances and the excursion rules

associated with these distances.

4.

The published diving profile rules (for example, the “V” profile

NORSOK).

5.

The final decompression process.

6.

The recommended proportions of gas for each phase.

Regarding the previously mentioned lack of scientific documentation, it

must be remembered that, since antiquity, it has been common

practice for scientists to publish the conclusions of their work to the

scientific community before releasing them to the public. This practice,

which aims to ensure that the described study is scientifically

accurate, has also allowed us to refer to these works and use them

for further research. Scientists involved in creating diving

decompression procedures are accustomed to working this way. For

example, the latest explanations of the current evolution of the US Navy

tables are presented in the documents “Testing of Revised Unlimited

Duration Upward Excursions During Helium-Oxygen Saturations Dives”

published by Dr. Thalmann in 1990, “VVal-79 Maximum Permissible

Tissue Tension Table for Thalmann Algorithm Support of Air Diving”

published by Doctors Wane Gerth and David Doolette in 2012, and

“Manned Validation of a US Navy Diving Manual, Revision 7, VVal-79

Schedule for Short Bottom Time, Deep Air Decompression Diving”

published by Doctors Brian Andrew and David Doolette in 2020. The

studies that resulted in the creation of the Normam-15/DPC-2021 are

described in a document titled “Deep diving: The Comex experience”,

which has been written and published by Jean Pierre Imbert at the

Bergen conference in September 2005. More recently, Dr. Risberg, the

lead author of the editorial team of the Norwegian diving and

decompression tables (NDDT), has published a document entitled

"NDDT—Probability of Decompression Sickness", which details the

conceptual process undertaken by the team to create these

decompression tables.

Some may argue that the gas values mentioned in the Normam-

222/DPC have been in force in Brazilian waters since 2016 and that no

decompression incidents have been publicly reported, so this modified

procedure can be considered safe. However, this argument is

fallacious for the following reasons:

•

First, there is no data to verify this point accurately, considering that

many events may have gone unreported by companies and the

divers experiencing them.

•

Second, even if no visible decompression sickness incidents have

been reported, it does not mean that divers have not suffered from

undetected decompression sickness or various stresses related to

decompression that could lead to medical complications later. For

example, in a document titled "Saturation Diving: Physiology and

Pathophysiology," Alf O. Brubakk, John A.S. Ross, and Stephen R.

Thom state that while testing the US Navy's "Unlimited Excursion"

tables from 300 to 250 meters of seawater (msw), results showed

that all divers had significant amounts of vascular gas bubbles in

the carotid artery, the blood vessel supplying the brain. However,

none of the divers exhibited acute clinical symptoms. This

phenomenon was confirmed during upward excursions from 300

to 250 msw in an experimental saturation dive, where Dr. Brubakk

et al. found arterial bubbles in the carotid arteries of all six

participants, without resulting in clinical cases of neurological

decompression sickness. However, post-dive examinations revealed

a minor cerebral lesion in the diver with the highest number of

carotid bubbles. Therefore, we can consider that the naked eye and

feeling are not sufficient to detect some accidents and that only

tools such as doppler, echocardiography, bioimpedance, urine

testing, salivary testing, blood testing, magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI), etc., allow specialists to detect the effects of such not visually

detectable decompression accidents. The recent studies

“Commercial Divers’ Subjective Evaluation of Saturation”, “Vascular

Function Recovery Following Saturation Diving”, and “Hydration Status

during Commercial Saturation Diving Measured by Bioimpedance

and Urine Specific Gravity”, available in our database, are examples

of the use of such tools to identify the various stresses and not

visible decompression problems in relation to saturation diving.

To the best of our knowledge, there has not been any study based

on such research protocols that concludes that changing the initial

PPO2 of a COMEX-based saturation procedure to US Navy PPO2

values does not affect divers.

Based on the above and the elements mentioned in the previous

section, it is evident to us that the Brazilian authorities made several

undocumented and inconsistent modifications to key points, resulting

in the creation of a new decompression procedure with some critical

parts lacking scientific evidence.

In addition to the problem above, which results in the procedures

Normam-222/DPC no longer being compliant with the original ones

published in 2011, we must consider that numerous elements are

missing for an extended period of time, which demonstrates issues

regarding document control procedures and an obvious lack of

reactivity to address them. Consequently, we have considered that

these procedures cannot be viewed as relevant for the operations for

which they were created, and that the only procedures to be

implemented remain the NORMAM-15/DPC-2011, faithfully described

in the CCO Ltd diving management study #5, except in Brazilian

waters, where the authorities may impose their unsuitable

modifications.

Therefore, while the adoption of the initial saturation procedures by the

Brazilian authorities in 2011 could be seen as an example to follow by

national bodies, the modifications they implemented since 2016 and

the lack of reactivity they demonstrate to correct issues should be

regarded as an example not to follow, which opens to discussion

regarding the duties of states regarding the publication and

implementation of standards.

For an accurate discussion, it is essential to remember that in an "ideal

world," governments are expected to establish standards based on

scientific research, which they either fund or adopt, in line with their

role as judges and arbitrators, ensuring that the procedures applied

within their territory adequately protect all citizens. These standards

are then adopted by companies and professional organizations, which

use them to develop their guidelines, and can be shared with other

national and international organizations.

Most governments are also engaged in the application of the World

Medical Association’s “Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for

Medical Research Involving Human Subjects”. This declaration, first

published in 1964 to prevent unethical medical practices and amended

in 1975, 1983, 1989, 1996, 2000, 2008, 2013, and 2024, is composed

of 37 articles classified into topics, among which the following refer to

procedures to implement when undertaking new studies involving

human participants:

•

Article 12, in the section “General Principle”, states that medical

research involving human participants must be conducted only by

individuals with the appropriate ethics and scientific education,

training, and qualifications, in addition to the fact that such research

requires the supervision of a competent and appropriately qualified

physician or other researcher. It also states that scientific integrity

is essential in medical research involving human participants and

that involved individuals, teams, and organizations must never

engage in research misconduct.

•

Article 17 in the section “Risks, Burdens, and Benefits” says that all

medical research involving human participants must be preceded

by careful assessment of predictable risks and burdens to the

individuals and groups involved in the study in comparison with

foreseeable benefits to them and other individuals or groups

affected by the condition under investigation. Also, measures to

minimise the risks must be implemented, and the risks and

burdens must be continuously monitored, assessed, and

documented by the researcher.

•

Article 18, also in the section above, states that physicians and other

researchers may not engage in research involving human

participants unless they are confident that the risks and burdens

have been adequately assessed and can be satisfactorily managed.

In addition, when the risks and burdens outweigh the potential

benefits or there is conclusive proof of definitive outcomes,

physicians and other researchers must assess whether to continue,

modify, or immediately stop the research.

•

Article 21 in the section “Scientific Requirements and Research

Protocols” mentions that medical research involving human

participants must have a scientifically sound and rigorous design

and execution that is likely to produce reliable, valid, and valuable

knowledge and avoid research waste. It also states that research

must conform to generally accepted scientific principles and be

based on a thorough knowledge of the scientific literature and other

relevant sources of information.

•

Article 22, which follows Article 21 in the abovementioned section,

states that the design and performance of each research study

involving human participants must be clearly described and

justified in a research protocol. This protocol should include a

statement of the ethical considerations involved and indicate how the

principles in the Declaration have been addressed. Additionally, it

should provide information regarding aims, methods, anticipated

benefits, potential risks and burdens, qualifications of the

researcher, sources of funding, any potential conflicts of interest,

provisions to protect privacy and confidentiality, incentives for

participants, provisions for treating and/or compensating

participants who are harmed as a result of participation, and any

other relevant aspects of the research.

•

Article 23 in the section “Research Ethics Committees” mentions

that the protocol must be sent for review, comments, guidance, and

approval to a relevant research ethics committee before starting the

research. That this committee operates transparently and maintains

independence from outside influences, in addition to having enough

resources. Its members must be well-educated, trained, qualified,

and diverse to assess the research effectively, suggest changes,

and eventually withdraw approval and suspend ongoing studies.

Finally, this article concludes that no protocol changes can occur

without committee approval.

•

Article 26 in the section “Free and Informed Consent” states that

each potential participant must be adequately informed in plain

language of the aims, methods, anticipated benefits, possible risks

and burdens, qualifications of the researcher, sources of funding,

potential conflicts of interest, provisions to protect privacy and

confidentiality, incentives for participants, provisions for treating

and/or compensating participants harmed as a consequence of

participation, and any other relevant aspects of the research. The

potential participant must be informed of the right to refuse to

participate in the research or withdraw consent to participate

without reprisal. Special attention should be given to the specific

information and communication needs of individual potential

participants and the methods used to deliver the information.

These articles are reused by competent international bodies such as

the “Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences

(CIOMS)” and UNESCO and are reproduced in the Brazilian Ministry of

Health's "Operational Manual for Research Ethics Committees (Manual

Operacional para Comitês de Ética em Pesquisa)". So they should be

applied in Brazil when research is undertaken to issue a new

decompression procedure.

Given the absence of any documentation substantiating the

implementation of these articles, it can be deduced that they have

likely not been applied for the study of these Normam-222/DPC

saturation decompression procedures and the previous 2016 and

2021 revisions. This is likely due to a lack of awareness among the

individuals who imposed these US Navy procedures and probably

believed their actions were optimal.

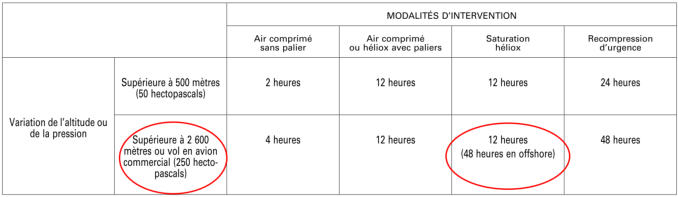

It is worth noting that, although the Brazilian government is highlighted

here, we must recall that it is not the sole entity to publish documents

with inconsistencies made by civil servants who lack sufficient

knowledge to fully understand what they write. For example, we can

note that in Section 9 of Chapter 3, “Procedures et Moyens de

Decompression”, of the “Arrete du 14 mai 2019 relatif aux travaux

hyperbares effectues en milieu subaquatique—mention A (Decree of

May 14, 2019, relating to hyperbaric work carried out

underwater—reference A)”, it is stated that a diver who has been

involved in an inshore or inland saturation dive should wait 12 hours

before being authorized to be transferred by plane with the cabin

pressure at 250 hectopascals (long-range flight), but that if this diver

had undertaken the same saturation with the same work offshore, the

standby time before flying the same distance becomes 48 hours.

Therefore, it appears that the individuals who wrote this document did

not understand that the standby time before flying is related to

decompression.

Other inconsistencies can be noted in this document.

This means that governments should employ experienced specialists

to compile and publish their directives, which must be based on

consistent reasoning and scientific evidence.

Due to the specific aspects of diving and ROV operations, some issues,

such as those related to decompression, may fall outside the

competencies of their employees. For this reason, it is common for

competently managed national organizations to appoint independent

bodies to compensate for this lack of expertise. For example, from the

1960s to the late 1990s, the French government commissioned COMEX

to develop its mandatory diving tables and related standards and

conduct research on diving physiology, which culminated in the Hydra

10 dive (reaching 701 meters) in 1992 (As mentioned above, it is

unfortunately no longer the case). It has also been the case in the

United Kingdom, where the Health and Safety Executive (HSE)

appointed organizations such as "Unimed Scientific Limited" to

undertake physiological research and provide documented guidelines

on diving procedures. It is still the case with the Norwegian

government that appoints the "Norwegian Underwater Institute" (NUI)

for similar tasks, or the Polish government that interacts with the

"Polish Hyperbaric Medicine and Technology Society", or the United

States administrations, such as OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health

Administration) and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration), that refer to the diving procedures published by the

US Navy.

These appointed organizations are distinguished by their ability to

provide documentation that adequately describes and supports the

standards they have issued, and to give the names of their authors.

This is, for example, the case of Dr. Valerie Flook, who is known to have

signed numerous UK-HSE documents and, more recently, those

published by NUI, the Polish Hyperbaric Medicine and Technology

Society, or the US Navy (see in our database).

Contrary to these examples, we are witnessing a phenomenon where

some states create mandatory standards solely based on guidelines

from various professional organizations they adopt without prior study

or consultation with competent experts, often relying only on unverified

assumptions. It is true that, due to their small size and limited budgets,

some of these states lack adequate resources and expertise regarding

underwater operations. However, nothing prevents them from

occasionally engaging advisors who could assist in selecting existing

standards and guidelines suitable for the norms they aim to establish.

We are therefore faced with a scenario opposite to the ideal, which

raises questions about the validity of the standards these states

create, adopt, publish, and approve.

Let's be clear: The problem does not lie with the professional

organizations that publish guidelines to defend their viewpoints and

achieve a certain harmony regarding the procedures applied by their

members, as they are entirely within their role by doing so. The issue

stems from the inability of some states to make appropriate decisions

for ensuring the reliability of the information they provide, which

typically falls under their responsibilities, due to the problems

mentioned above.

This often leads to illogical national standards that may then be taken

as references, encouraging the spread of other inadequate

procedures whose authors cannot justify the reasons behind them. As

these improperly founded norms accumulate erratically, they can also

become circular references, leading to a monoculture that lacks

adequate questioning of the validity of the promoted procedures. This

creates a chaotic situation where national bodies, which should serve

as references, lose their prerogatives to pressure groups, as

previously explained in the article "About Standards," published in this

section of the website in January 2023.

It is worth noting that this lack of scientific and technical supporting

documents is not only a fact of only these governments, as we can

also highlight that some well-known supranational organizations, such

as the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the International

Organization for Standardization (ISO), the European Standards, and

others commonly referenced, are known to issue standards for which

we cannot see the scientific and technical studies used or who

compiled them (except for ISO regarding this last point), which

contrasts with the virtuous behaviour we advocate, and some

organizations and states mentioned above have demonstrated that it

can be implemented.

Such a chaotic situation should not continue, or the foundation on which

safety procedures rely will vanish, potentially leading to accidents due

to a loss of fundamental knowledge and people applying rules without

understanding their basis.

Therefore, we advocate for national, supranational, and international

organizations to be exemplary in how they present their standards,

which should be thoroughly documented and validated by the scientific

and professional communities. Remember that scientific references

are now easily accessible, as many free databases are available to the

public, making it easy to provide them.

Of course, implementing such practices may be challenging for some

personnel who have worked for some time in organizations

accustomed to imposing rules without explanation or discussion. It is

therefore the responsibility of the hyperbaric workers' community to

strongly request that the standards imposed on them are based on

recognized scientific studies, cited in published documents, and

endorsed by competent scientists and the communities involved with

these norms. In other words, we can agree that those who issue

national and international standards should enforce them only if they

can explain the reasons for the norm they want to publish, on what

these new norms will be beneficial for the community, on which

scientific studies these norms are based, whether these studies have

achieved consensus regarding their conclusions, and whether the

norm will not conflict with existing ones. Additionally, the names of the

people involved in the elaboration of standards should be mentioned, as

is customary in the scientific community. Therefore, if these elements

are not adequately provided, the new standard should not be

implemented.

The second point is that this evaluation revealed that while most parts

of the saturation procedures remain unchanged, and some

improvements, such as the respect of the biological cycle of the divers,

have been provided, the Brazilian authorities made the following

modifications, resulting in these procedures no longer being compliant

with the original ones published in 2011:

•

The initial PPO2 values during the decompression phase, initially

between 0.48 and 0.5 bar, have been reduced to 0.44 and 0.48 ATA.

These absolute atmosphere (ATA) values are those used by the US

Navy revision 7 (published in 2016) for the storage and ascent

phases. Taking into consideration that a scientist would have used

pascals or, alternatively, millibars, given that the table is written in

metric units, we have concluded that this modification has not been

performed by a scientist or a diving specialist accustomed to

decompression procedures. Additionally, recent procedures

designed by Jean Pierre Imbert for reputed companies that are

IMCA members show that the value of 480-500 mb has been

maintained with equivalent storage PPO2 values to those he initially

provided for the NORMAM-15/DPC-2011. Furthermore, studies such

as the paper "Evaluation of North Sea saturation procedures

through divers monitoring" show that these tables yield very

satisfactory results regarding oxygen and decompression stresses.

Therefore, the question can be raised about the safety

performances that can be expected from new decompression

procedures that continue to use the former rates of ascent but with

lower chamber PO2.

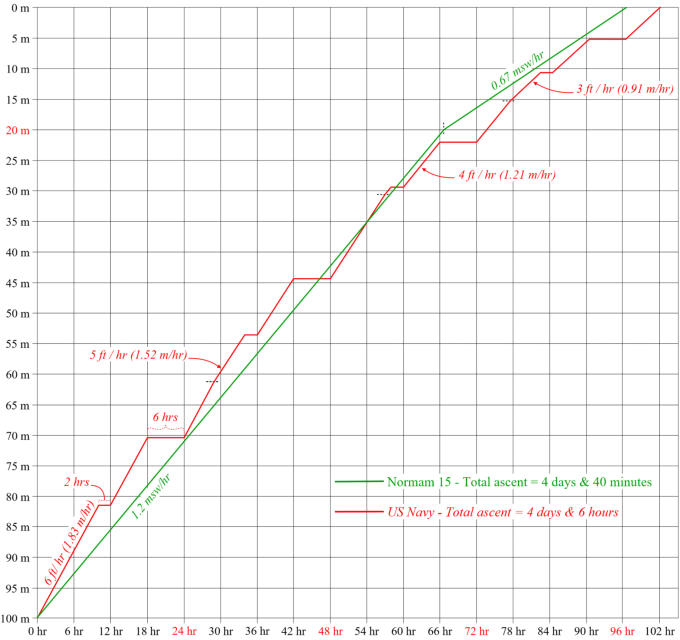

To further explain this point, it must be taken into account that the

decompression strategies of COMEX-based tables and US Navy

tables are not the same: While COMEX-based procedures such as

the Normam-15/DPC-2011 use slow, continuous, and uninterrupted

ascent rates (1.2 msw/hr from 350 to 20 m and 0.67 msw/hr from

20 m to the surface) with a PPO2 of 480 to 500 mbar after an at-

depth rest period in the living chamber (commonly called "storage")

with a PPO2 of 380 to 450 mbar, the US Navy procedures use

faster ascent rates interrupted by 8 hours of stops per 24 hours

divided into at least two parts, with a PPO2 between 0.44 and 0.48

ATA (445.83 mb - 486.36 mb) and the same PPO2 during the

"storage" period. We can note that these standby times (stops)

during the ascent compensate for the faster ascent rates

compared to the COMEX procedures (see the comparison of both

decompression curves below).

Therefore, taking into account that the decompression strategies are

different, we can consider that changing the PPO2 of the NORMAM-

15/DPC by adopting those of the US Navy resulted in creating a new

decompression procedure that should have been rigorously tested.

As a conclusion, it seems to us that no modification of these original

gas values was necessary and that this modification has been

imposed without the support of any published scientific study and

without consulting the lead author of the original procedure or

members of the scientific community, which the Brazilian

authorities implicitly confirmed in a message received on 07 August

2025, as they did not provide any documented answers to our

questions regarding this critical point.

•

The percentage of O2 during the final phase of decompression is

now limited to 21% instead of the initial 25%. While the 25% limit may

increase the risk of fire if an imprudent operator exceeds it, it

offers a comfortable operating range for the Life Support

Technicians (LST), which is significantly reduced with a limit to only

21%. Considering that the LST on duty will require a certain degree

of flexibility, we made the remark that the 23% value recommended

by IMCA, previously retained in the initial edition of the CCO Ltd

study #5, is balanced and appropriate. The Brazilian authorities

responded that the final part of the text was incorrectly edited and

should have stated that the ideal oxygen percentage must remain

within the range of 19% to 23%, with 21% as the recommended

value. Therefore, a correction is to be made to this already 9-year-

old text.

•

Note that the PPO2 values for the compression and storage phases

that were lost in the initial official 2011 document, despite being

provided by the author in the initial COMEX procedure, are still

missing in the NORMAM-222/DPC revision. The Brazilian authorities

did not comment on our remark regarding this point.

•

The excursion combination #7 “Exceptional upward excursion

followed by a standard upward excursion” has disappeared in the

document NORMAM-222/DPC. The Brazilian authorities said that it

was due to an editorial oversight at the time of publication, which

had not been formally identified until now.

Courtesy of Fabrice Pipault

Christian CADIEUX & Doctor Jean Yves MASSIMELLI